Anthropology By Children (ABC) and Islington Council: a CAPE fellowship collaboration case study

⌚ Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Dr Kelly Fagan Robinson

Leverhulme and Isaac Newton Trust ECR Fellow, University of Cambridge

Imogen Resnick

Fairness and Equality Officer, Islington Council

In this post, anthropologist Kelly Fagan Robinson and policy officer Imogen Resnick discuss the initial findings from the Anthropology By Children (ABC) pilot in schools, and discuss what they have learned together about the ways in which inclusive research can provide a rich foundation for successful collaboration between academics and policy-makers and a better future for participants.

CAPE Fellow and Strategic Lead for Policy and Equality at Islington Council, Hayley Sims, was first approached by Anthropologist and CAPE affiliate Kelly Fagan Robinson (Leverhulme and Isaac Newton Trust ECR Fellow, University of Cambridge) in Autumn 2021 to see whether there might be synergies between Islington’s areas of interest and Robinson’s ongoing research. Robinson was working as a volunteer for Citizens Advice Islington as part of her three-year study on the ways people ask for help in the UK. In the same building just two floors away, Sims and colleague Imogen Resnick (Fairness and Equality Officer) were about to embark on Let’s Talk Islington (1), Islington Council’s biggest-ever public engagement programme into inequality, engaging over 6,000 Islington residents (11/2021-09/2022). The Let’s Talk team aspired to understand local people’s lived experiences of inequality but knew there was not a ‘one size fits all’ engagement strategy. Because traditional research approaches can lack mutual exchange of knowledge between researcher and participant, Let’s Talk invested heavily in innovative research approaches which built trust, generated mutual value, and empowered marginalised voices to have ownership over their own stories. Robinson’s work on impediments to seeking support and the limits of communication were a natural fit.

Let’s Talk supported Robinson’s research access to one of Islington’s most underrepresented demographics: children. In Islington, 28% of children under 16 live in low-income households (2) – the 10th highest for child poverty in the country – and over 43% of primary school pupils in Islington’s schools are eligible for the deprivation Pupil Premium. The schools in which the pilot was conducted had 60% of children on average using English as a second language, rising in one school to more than 78%, with an average of 46% of children on free school meals (3). Within this context, Robinson developed Anthropology By Children (ABC), a pioneering initiative piloted for year 6 children in five local schools, including state and independent sector schools, and schools for children who have Special Educational Needs (SEN). Year 6 students were trained in qualitative research methods typically taught in an undergraduate Anthropology degree. Children learned ethnographic methods – ethnography literally meaning ‘life charting’, documenting their experiences using photography, drawing, and writing. As pupils learned and employed these approaches to communicate their experiences inside and outside school, they also learnt how to listen and be listened to, reinforcing the value of their own voices. In addition to providing children across the attainment spectrum with a useful research and communication toolkit, ABC yielded key insights into the lives of Islington’s young people in the terms they used to express their perspectives, crucial for the understanding of those who do not directly share their experiences. This has had significant implications for the horizons of the ABC students, in the ways they conceive of the value of their contributions, how they can make heard the reality of inequalities in their lives, giving shape to what they believe possible for their futures (4).

The ABC approach to inclusive research

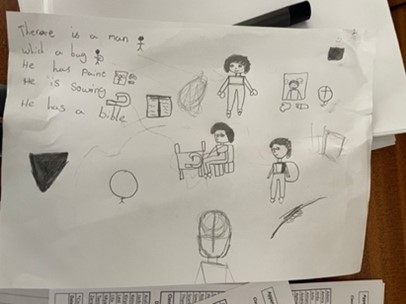

Robinson begins ABC by explaining that anthropology – the study of what it means to be human – is primarily about listening and playing detective, uncovering clues about the different things that matter to people in particular social and spatial contexts. The children were called on to use their detective skills to find clues in a short POV film which walks alongside a person as they arrive at a building to try to understand who the person is – where they live, how their surroundings impact on everyday life, their beliefs, their passions, their personal rules; they did so based on what they saw in only one viewing of the film. The pupils wrote or drew “fieldnotes” as they watched the clip and compared what they noticed about how hard it is to know a person having only ever seen them one time, the biases that people carry, and how these impact upon interpretations of people and situations.

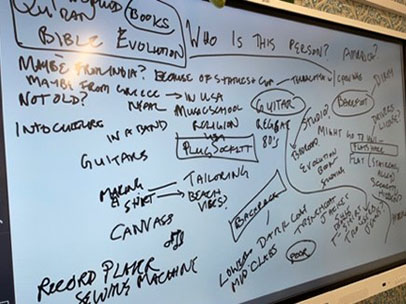

Notations from class discussion answering: Who is this person?

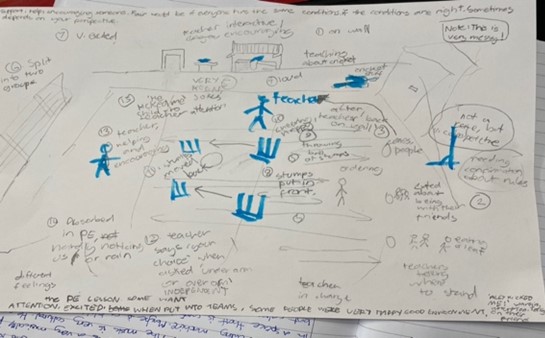

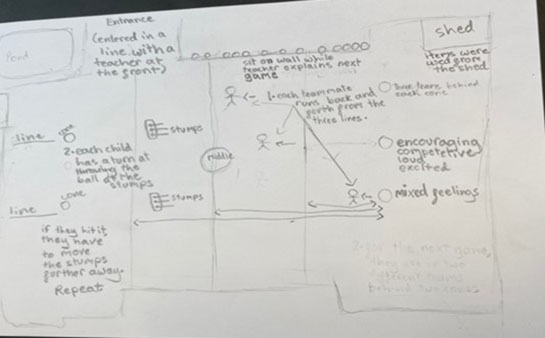

During the following session, the ABC students drew maps of other students at play. They mapped who listened to whom, who was the leader, who was excluded/included, what the rules were and who was breaking them. Pupils learned to chart these proxemics – the study of physical positioning of people in social groups – to make differences in power, leadership, hierarchy visible.

Examples of proxemic maps

The pupils also learned to interview using open questions, and in the following session voiced their partner’s stories using the first person in front of their partner, feeling the weight of the responsibility of voicing someone else’s life experiences. The clubs culminated in a photovoice project, in which they used cameras to take photographs of spaces and objects to storyboard their time in school, what they would miss, and the things they would change if they could.

What was learned by engaging in this way?

Through use of ABC as a co-constructed way to gather data about students’ experiences, Robinson was able to see clear disparities in the everyday lives of the children as told by those children. When asked what would you change? whether that change pertained to resources in the area, their schools, things in their family homes or other spaces, the children clearly addressed inequalities in insightful and graspable ways that offered feasible inroads for change.

One school’s photovoice project brought to light that one of the students, known to be diligent and committed to their studies, never realised that during lockdown, the one time the children were required to login for attendance registration in the morning was not the only class that they were meant to be attending. The student had thought that that session of 30-45 minutes was the only interface with school during the day, when in fact six hours of programmed learning had been offered. This prompted a discussion by the students about which lessons they had attended being directly corollary to their number of care responsibilities at home, their access to computers, data availability/affordability, as well as English proficiency.

Across three schools involved in the study, segregated playgrounds/playtimes came up frequently. When schools began to reopen after the first UK Covid lockdown, schools were required to ‘bubble’ the year groups (keeping the same group of children together everyday) to prevent infection spreading between groups. Unfortunately, since Covid first began, many of those divisions have been sustained in the schools. The children discussed how schools have become less connected across the year groups. In one location, a school for Deaf children and an academy school who had in the years before the pandemic shared common spaces to teach both cohorts of children sign language and Deaf awareness but also to play and eat together, even sharing joint assemblies. Following the Covid lockdowns these programmes ceased to operate because of social isolation bubbles, and shared learning had not returned as a priority. The children hoped the joined-up sessions would return.

Personal reflections from a research perspective

Robinson notes that collaboration with Islington has reduced time contending with gatekeeping that often significantly prolongs pre-field research. In a post-Covid landscape access to and observation of pedagogical practices as well as the social relations between these and officers of the school, the council, third sector leaders, teachers, and MPs, has also enabled a far more holistic research approach, deeply enriching what is analytically possible. The schools’ anthropology projects could undoubtedly be conceived of as a form of ‘nice to have’ engagement. However, through focusing on not simply extracting information, but instead on teaching children to use the ethnographic methodologies themselves, the project has both yielded richer data than if the researcher has conducted interview. It has also begun to engender a form of citizen science which is shaping the lives of young Islington locals and their awareness of possible action.

Teachers have commented throughout the ABC sessions that they have many students who they know are capable, but who struggle to speak out or making their perspectives known in class. They said that the visual mediums the children learned during the ABC clubs encouraged those students less likely to talk in class to present their experiences in visual ways. Because of this, the students were more comfortable and therefore took on leadership roles, presenting not just in-class, but on film and live onstage in school assemblies.

Personal reflections from a policy perspective

Through the Let’sTalk engagement, professionals working with young people stressed the negative impact inequality has on poorer children’s access to cultural opportunities, self-belief, and interest in education. Deprived children suffer not only the effects of financial poverty but also from a poverty of aspiration: the sense that doing well in school or partaking in society will not improve their available choices. Robinson’s pilot created a unique opportunity: children from less advantaged backgrounds gained access to knowledge and modes of expression typically reserved for elite university students, inspiring them with visions of new pathways for their futures. Additionally, hosting an academic from one the world’s best universities exposed young people to new possibilities of how their lives could develop as well as the value their voices hold in terms of citizenship and transformation in the locality but also far beyond.

Challenges remain, notably academic and policy timelines; the reality of pressures for local authorities to deliver for residents quickly with increasingly straitened resources, while long-term research necessarily works to longer timelines. There is also need for integration between more abstracted analytical insights and urgent attention on what is practically attainable and politically possible. And of course, there are differing funding dynamics at play. This partnership, however, proved to be a highly positive experience that yielded innovative methods for empowering children, through amplifying their voices with potential for far reaching applications for other less-heard from members of the local Islington population.

Unlocking closed doors

Anthropologists are trained that research participants should transform the researcher’s concepts rather than the other way around, and to a certain extent this also holds true in policy formation; citizen stakeholders are the people who inform transformation of policies. The project is only just beginning, but it is working toward culminating in a broader understanding of citizen engagement from age 10+, looking at ways of embodying citizenship, fostering individual agency, and achieving different ways of voicing one’s own story and directly impacting community transformation; these are also key objectives discussed by Islington Council’s Inequalities Taskforce. Additionally, through seeking out the partnership using the CAPE fellowship as a resource for finding a local government whose research and evidence agenda aligned with the researcher’s project, this collaboration has had the privilege of directly feeding into Islington’s inequality engagement programme including the Inequality Taskforce, Let’s Talk Islington, and their upcoming inequalities summit set for early 2023.

References

(1) https://www.islington.gov.uk/about-the-council/vision-and-priorities/lets-talk

(2) https://www.islington.gov.uk/-/media/sharepoint-lists/public-records/communications/information/adviceandinformation/20212022/20220223stateofequalities20221.pdf?la=en&hash=61024346CDF4CFA2C9B3E0970A973FC656C55092

(3) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pupil-premium/pupil-premium

(4) Koch, Insa, and Deborah James. “The state of the welfare state: Advice, governance and care in settings of austerity.” Ethnos 87, no. 1 (2022): 1-21.