A typology and discussion of interactions between CAPE academic policy engagement mechanisms

⌚ Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

Milena Santos

CAPE Coordinator, University of Cambridge

Robyn Parker

CAPE Project Manager

CAPE has been running for two years now, and in that time we have observed interactions between our policy engagement mechanisms which we did not necessarily anticipate at the outset. We’ve developed a typology of these interactions which we hope can provide valuable insights into how having multiple, connected project mechanisms can support academic-policy engagement.

Key findings

- Having resources and capacity to manage multiple ways of doing academic policy engagement can result in each mechanism mutually reinforcing one another. This leads to greater volume and depth of engagement than each of the mechanisms individually.

- There are four different ways in which CAPE’s policy engagement mechanisms have interacted in unanticipated ways throughout our project.

- Interactions between the mechanisms have allowed us and our stakeholders to dive deeper, branch out and solve problems.

What are CAPE mechanisms?

CAPE project has four mechanisms through which we undertake policy engagement:

- Fellowships. We offer bidirectional policy fellowships: a flexible professional development programme for those who work in public policy, local and national government; and individual fellowships within policy organisations for researchers, academics or professional services staff based at CAPE universities.

- Seed funding. Our Collaboration Fund supports projects that have been co-developed by researchers with at least one policy partner to address a specific policy need. The ‘policy challenge’ element of the fund enables policy stakeholders to put forward specific challenges to which researchers can respond.

- Knowledge exchange events. We deliver a range of different, co-created knowledge exchange and engagement events to help build academic policy dialogue around particular topics and understand how best to respond to evidence needs.

- Training. We work with researchers and with policy professionals to understand and respond to specific skills training needs in order to strengthen academic policy engagement.

Typology: the interactions between CAPE policy engagement mechanisms

We took stock of the project activities implemented so far and mapped examples of mechanism interactions. This mapping highlighted the multiplicity and complexity of the interactions that have emerged since the start of CAPE.

On this basis, we’ve identified four types of interactions to describe the way in which our mechanisms act together.

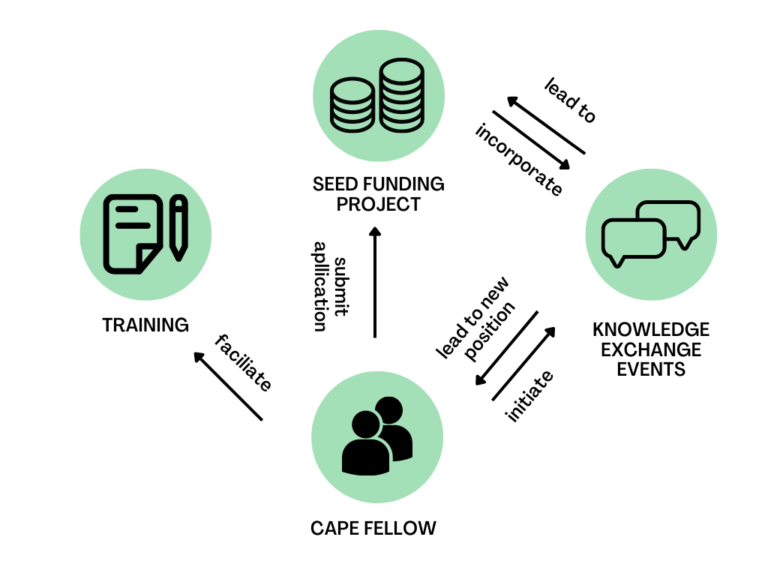

1. Follow-on interactions

‘Follow-on interactions’ are when one CAPE mechanism with a policy stakeholder led to another activity on the same topic, responding to the appetite of policymakers and researchers for additional engagement . For example, after convening roundtables on the concept of ‘good work’ with Islington (falling under our ‘knowledge exchange’ mechanism), we recognised the space for further work on this through a ‘policy challenge’. Follow up activities allow policy professionals and researchers to strengthen relationships and further explore issues of mutual interest. In this sense, having multiple engagement mechanisms provides additional avenues where there’s a desire for follow-up.

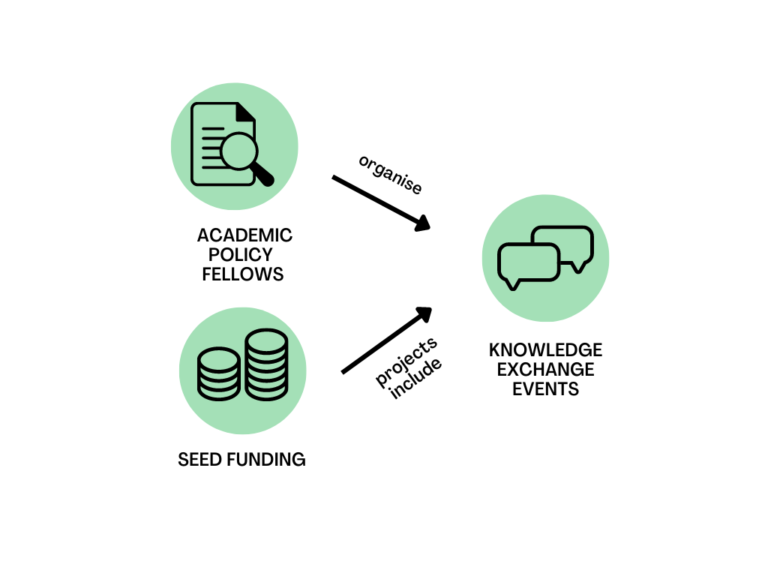

2. Interactions by design

Connections between different mechanisms have also intentionally been built into many of our activities from the start – we define these as ‘interactions by design’.

For example, several of our policy fellowships for academics specify that fellows will organise knowledge exchange events as part their appointment. CAPE policy fellow Darren Sharpe has organised a variety of knowledge exchange events in collaboration with Newham council. Interactions by design allow researchers and policy makers to explore topics in more depth and collaborate in different ways.

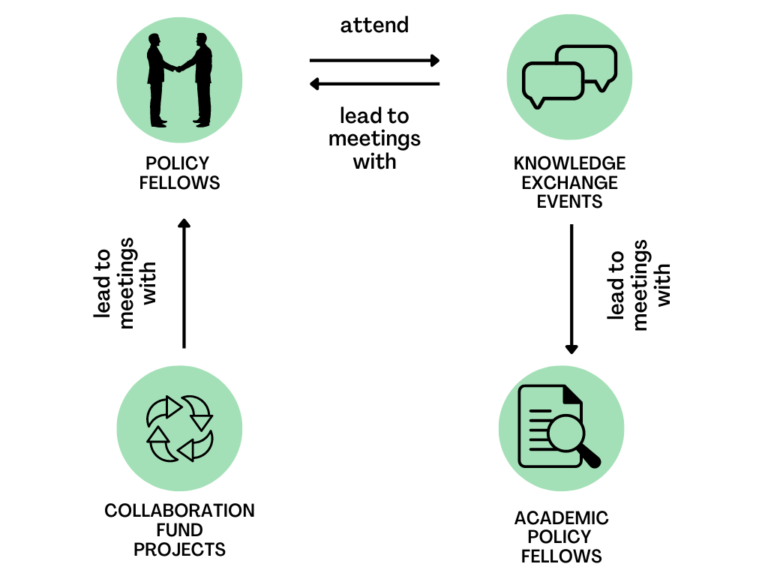

3. Network interactions

The previous two types of interactions outlined interactions between CAPE mechanisms that allowed academics and policymakers to explore specific topics in more depth . In comparison, ‘network interactions’ arise from the network created by CAPE and lead to a wider breadth of activities. For example, CAPE Policy Fellows are often invited to and attend knowledge exchange events organised within the CAPE network. As such, fellows can engage with topics beyond their specific focus. Network interactions can therefore lead to unanticipated engagement and allow our stakeholders to branch out and explore wider issues around academic policy engagement.

4. Problem-solving interactions

One of CAPE’s aims is to trial what works – and what doesn’t – in academic policy engagement. Not all activities that we initiated were immediately successful within the chosen mechanism. Having different potential mechanisms enables us to find the right approach for a given problem/issue/engagement. For ‘problem-solving interactions’, activities are connected by a shared topic but the aim is not to dive deeper but to solve a problem with the initial activity set-up. In one example of this type of problem-solving interaction, an unsuccessful collaboration fund application was re-developed into a policy challenge. While being exploratory and innovative, the initial collaboration fund application was not a suitable match for the collaboration fund mechanism. We built on the innovative approach of the proposal and, in collaboration with academics and policy partners, developed it into a policy challenge. This type of problem-solving interaction can be beneficial for finding alternatives and incorporating stakeholder feedback into activities.

Discussion: how interactions between mechanisms are supporting academic policy engagement

Across CAPE, we have found that academic policy engagement benefits from the availability of several mechanisms. Having resources and capacity to manage multiple ways of doing academic policy engagement has resulted in them mutually reinforcing one another, and in turn has led to greater volume and depth of engagement than each of the mechanisms individually. These interactions between the mechanisms have allowed us and our stakeholders to dive deeper, branch out, and solve problems.

Our experience through CAPE supports the view that coordination and capacity are critical for academic policy engagement (Campbell 2011; Schutt et al. 2012). The interaction between the different CAPE mechanisms described above has been facilitated through our project infrastructure, with a team of coordinators who can link activities across our partner universities. We have benefitted from being able to draw on complementary strengths across our consortium in different mechanisms. This means that the project can be more flexible and responsive to the needs of our stakeholders. It also means that the project has leveraged our diverse attributes to create a more comprehensive and effective approach to academic policy engagement.

We are also observing that CAPE activities are adding to the individual and collective knowledge, skills and attitudes that enable academic and policy stakeholders to engage in academic policy engagement. This is contributing to an increased sense of confidence and capability among researchers, policymakers and knowledge mobilisers, which in turn is enabling them to engage in further activities (often through other mechanisms). For example, CAPE Policy Fellowships have often been the first opportunity for junior civil servants to engagement with academic researchers. Some of our Policy Fellows then take their learning further by continuing their engagement through other mechanisms.

Finally, our experience also suggests that interactions between mechanisms matter but so do local contexts and capabilities. Interactions have not occurred at all CAPE partner universities to equal degrees and volume seems to depend on timing, availability of expertise, appetite from policy partners and the availability of budget. Our learning suggests that universities with higher levels of existing academic policy-engagement might observe more mechanism interactions than those with newer policy units, which might be addressed by fostering closer collaboration between institutions as opportunities for new activities arise It should be noted that not all universities will have capacity to lead multiple different streams of engagement which might improve as policy units grow and develop.

References

Schut M, van Paassen A, Leeuwis C, Klerkx L. Towards dynamic research configurations: A framework for reflection on the contribution of research to policy and innovation processes. Science and Public Policy. 2014;41(2):207-18.

Campbell D, Donald B, Moore G, Frew D. Evidence check: Knowledge brokering to commission research reviews for policy. Evidence and Policy. 2011;7(1):97-107.