Lessons from literature and practice: how to support successful academic-policy engagement

Ariana Darvish

CAPE Postdoctoral Fellow

Sarah Chaytor

CAPE Co-Investigator

Robyn Parker

CAPE Project Manager

There has been increasing scholarly investigation of academic-policy engagement in recent years. This has accompanied the growth in knowledge exchange activities between academics and policymakers. With the academic-policy landscape rapidly evolving, understanding what is necessary for – and what constitutes – success becomes more important.

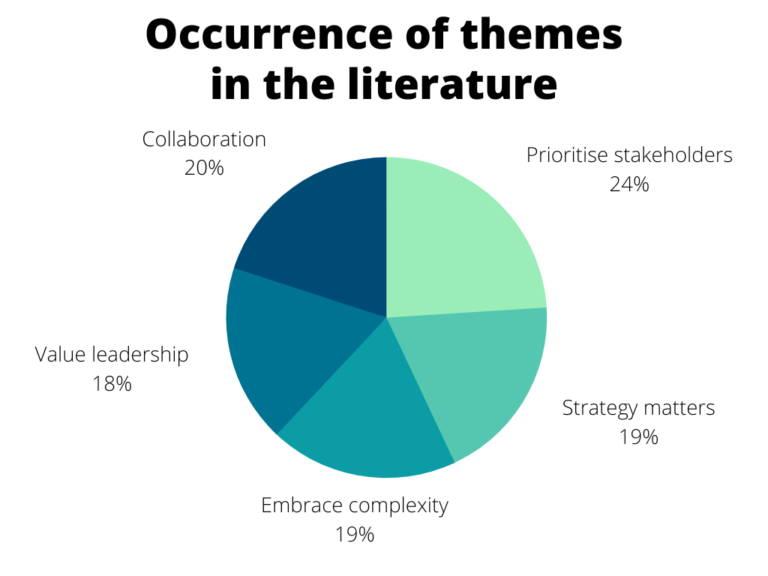

Investigating ‘what works’ for academic-policy engagement is one of the key objectives of CAPE. With that in mind, we’ve been investigating what common insights emerge from the growing body of literature on academic policy engagement. We reviewed the literature on academic policy engagement from a variety of disciplines – in particular, medical, environmental, psychology, and business and management – in 1475 databases (1995-2002). We identified 68 publications concerning academic policy engagement and a further 180 items of grey literature (narrowed to 15). Most of these studies explore the gap between the development of evidence and its use in practice, seeking to overcome the barriers leading to this. The numbered bibliography is provided below and cross-referenced throughout this blog.

At the same time, we’ve been reflecting on our experience in delivering CAPE over the past two years and some of the common themes that have been emerging. These largely align with the themes we’ve identified in the literature, so drawing from both the literature and our practice, we’ve identified five key considerations in supporting successful academic-policy engagement.

1. Prioritise stakeholder engagement

This is probably an obvious point for many of us working in the academic-policy engagement world – but that doesn’t take away from its central importance, which comes out clearly in the literature and from our experience in CAPE. Early and sustained engagement is fundamental to building understanding and trust, identifying shared priorities and objectives, and exploring different knowledge exchange and engagement activities. There are of course many different approaches to stakeholder engagement and it is not yet clear if some are more successful than others. It is also true that we are still discovering how to ensure that stakeholder engagement is always as diverse as possible.

"This is probably an obvious point for many of us working in the academic-policy engagement world - but that doesn’t take away from its central importance… early and sustained engagement is fundamental"

Above all, we’d emphasise that effective stakeholder engagement takes time and effort, and needs foregrounding, rather than being treated as an add-on (1, 2). This means allocating resource for such engagement and recognising that it needs sustaining over time, not operating as an isolated one-off (1, 3-6). For CAPE, this has meant ensuring that the project coordinators at each partner institution spend a significant amount of time and effort on building and sustaining stakeholder engagement (it thus accounts for a fairly sizeable proportion of our project resource) (7, 8).

Some of the interventions we’ve been exploring around stakeholder engagement include embedding co-production with local communities (9-15) in a project taken forward through a CAPE Policy Fellowship with the London Borough of Newham exploring citizen participation; and convening different local actors and institutions to share insights and co-develop solutions throughout the process of delivering the Oldham Economic Review.

Key articles include:

Martin S, Boaz A. Public participation and citizen- centred local government: Lessons from the best value and better government for older people pilot programmes. Public Money and Management. 2000;20(2):47-54.

Borst RAJ, Kok MO, O’Shea AJ, Pokhrel S, Jones TH, Boaz A. Envisioning and shaping translation of knowledge into action: A comparative case-study of stakeholder engagement in the development of a European tobacco control tool. Health Policy. 2019;123(10):917-23.

Lancet T. Getting political with evidence-based policy 2006 [Available from: https://odi.org/en/insights/getting-political-with-evidence-based-policy/.

2. Strategy matters

A clear strategy which recognises the different roles of multiple stakeholders is more likely to enable effective academic-policy engagement. Serendipity and seizing opportunities as they arise are of course important aspects of the reality of academic-policy engagement. But setting a clear strategy can better enable such serendipity (including more bottom-up approaches) whilst allowing prioritisation, particularly where resources and capacity are scarce (1, 4, 7, 8, 16-19).

This doesn’t mean being overly prescriptive or specific in defining activities (4, 16, 20-25). For CAPE our strategy has been to be as responsive as possible to policy demand and emerging opportunities (17, 20, 26-33) – therefore requiring a more agile approach to planning some project activities. But this agile approach is undertaken in the context of clear overall objectives and guided by our theory of change (34-37). And of course, moving towards the development of shared strategies on research and policy priorities can enable a more systemic approach – and improve evaluation of outcomes (16, 38-42) – to academic policy-engagement (20-25). For example, some of our ‘regional’ CAPE Policy Fellows have been working with the West Yorkshire Combined Authority and the Greater London Authority to map out policy priorities, evidence needs, and academic capacities to inform future strategy in regional academic-policy engagement.

Key articles include:

Boaz A, Hayden C. Pro-active Evaluators: Enabling Research to Be Useful, Usable and Used. Evaluation. 2002;8(4):440-53.

Hanney S, Kanya L, Pokhrel S, Jones T, Boaz A, Organization WH, et al. What is the evidence on policies, interventions and tools for establishing and/or strengthening national health research systems and their effectiveness?2020.

Tilley H. 10 things to know about how to influence policy with research 2017 [Available from: https://odi.org/en/publications/10-things-to-know-about-how-to-influence-policy-with-research/.]

3. Embrace complexity and uncertainty

The academic-policy landscape encompasses many complex, messy relationships as well as a plethora of non-linear processes underpinning engagement (1, 7, 43-49). This is compounded by considerable uncertainties around motivations and incentives on both sides, as well as rapidly changing policy priorities (7, 20, 50, 51). As described above, we have focused CAPE on being as responsive as possible in recognition of this. In practice, this has also meant embracing a certain degree of messiness in our own project structure and activities, which has relied heavily on the project team’s ability to work flexibly, managed unexpected challenges and respond to emerging opportunities (7, 48, 52-56).

So, this is about having the skills to manage such ambiguity and about building relationships with policy partners that can accommodate it (7, 34, 35, 48, 49). For example, CAPE’s partnerships with the Ministry of Justice and the London Research and Policy Partnership have enabled iterative discussions to identify specific policy needs and engagement activities. It is also undoubtedly enabled by dedicated resource and capacity – this degree of agility is highly challenging when engagement work is carried out in the margins of substantive work.

Key articles include:

Boaz A, Gough D. Complexity and clarity in evidence use. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2012;8(1):3–5.

Rivas C, Tomomatsu I, Gough D. The many faces of disability in evidence for policy and practice: embracing complexity. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2021;17(2):191–208.

Says S. To shape policy with evidence, we should celebrate both good practice and good theory 2021 [Available from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2021/01/20/to-shape-policy-with-evidence-we-should-celebrate-both-good-practice-and-good-theory/.

4. Value leadership in different forms

"Research leadership which takes account of societal needs can help to foster a culture of academic-policy engagement and valuing the different roles which contribute to it, including knowledge intermediaries."

Successful academic-policy engagement requires capabilities and skills at different levels: individual, organisational, and whole-system. Recognising the value of diverse capabilities and contributions at all levels, and the role of leadership in embedding particular approaches and ways of working, is important (11, 53, 57). For example, research leadership which takes account of societal needs can help to foster a culture of academic-policy engagement and recognition of the value of different roles which contribute to it, including knowledge intermediaries (47, 58, 59).

There are also implications for key actors in the system, including universities, research funders, and policy organisations, to consider in terms of capabilities at different levels. Firstly, how they can develop individual skills and capabilities and ensure appropriate incentives for individuals who undertake academic-policy engagement (60, 61). CAPE has been piloting a programme with policy teams within the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities to build team and individual capacity in evidence use and academic engagement. Secondly, what organisational structures and processes are required to enables routes for academic-policy engagement – the pairing scheme CAPE is piloting with GO-Science might offer one such route; others can be seen in the ESRC Policy Fellowships and Parliamentary Fellowships scheme, for example. And thirdly, how different components across the ecosystem can work together to ensure coordination and alignment (62-64) in enabling academic-policy engagement – initiatives such as UPEN, which connects a 100-strong network of universities with policy engagement opportunities, and IPPO, which synthesises and communicates evidence to inform policy considerations.

Key articles include:

Hanney SR, Kanya L, Pokhrel S, Jones TH, Boaz A. How to strengthen a health research system: WHO’s review, whose literature and who is providing leadership? Health Research Policy and Systems. 2020;18(1).

Walker A, Boaz A, Hurley MV. The role of leadership in implementing and sustaining an evidence-based intervention for osteoarthritis (ESCAPE-pain) in NHS physiotherapy services: a qualitative case study. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2020:1–8.

Traynor R, Dobbins M, DeCorby K. Challenges of partnership research: Insights from a collaborative partnership in evidence-informed public health decision making. Evidence and Policy. 2015;11(1):99-109.

5. Collaboration, coordination, capacity

It’s clear that embedding collaborative approaches – to engagement in general and to specific projects – really matters in terms of ensuring successful outcomes. As noted above, this collaboration is greatly enhanced when it is formed on the basis of early and sustained engagement between all stakeholders (7, 48, 65, 66). But it won’t necessarily happen automatically – our experience through CAPE, supported by our literature review – is that coordination and capacity are critical. By this, we mean that having dedicated knowledge brokers (7, 65) to bring different stakeholders together and foster engagement and networks, really helps to drive collaboration. And what such knowledge broker roles provide is dedicated capacity – to spend time building relationships, sustaining momentum, iterating collaborations, and checking-in frequently (7, 48, 65, 66). But of course, this role is frequently dependent on institutional systems and structures (15, 50, 59, 67, 68), including funding, training, and other incentives (7, 20, 50, 51).

Key articles include:

Campbell D, Donald B, Moore G, Frew D. Evidence check: Knowledge brokering to commission research reviews for policy. Evidence and Policy. 2011;7(1):97-107.

Oliver K, Hopkins A, Boaz A, Guillot-Wright S, Cairney P. What works to promote research-policy engagement? 2020.

van der Graaf P, Cheetham M, Redgate S, Humble C, Adamson A. Co-production in local government: process, codification and capacity building of new knowledge in collective reflection spaces. Workshops findings from a UK mixed methods study. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2021;19(1).

Conclusions

We will continue to share our learning and reflections – including from our ongoing monitoring and evaluation – for our delivery of activities. We’re also eagerly anticipating the findings from our independent evaluation, led by Transforming Evidence, into what works in terms of specific mechanisms to drive engagement. We are also going to intensify our efforts to tease out the precise role and contribution our project coordinators play as knowledge intermediaries in connecting partners, enhancing engagement and delivering impactful outcomes.

Literature

1. Hobin EP, Hayward S, Riley B, Ruggiero ED, Birdsel J. Maximising the use of evidence: Exploring the intersection between population health intervention research and knowledge translation from a Canadian perspective. Evidence and Policy. 2012;8(1):97-115.

2. Lövbrand E. Co-producing European climate science and policy: a cautionary note on the making of useful knowledge. Science and Public Policy. 2011;38(3):225-36.

3. Martin S, Boaz A. Public participation and citizen- centred local government: Lessons from the best value and better government for older people pilot programmes. Public Money and Management. 2000;20(2):47-54.

4. Borst RAJ, Kok MO, O’Shea AJ, Pokhrel S, Jones TH, Boaz A. Envisioning and shaping translation of knowledge into action: A comparative case-study of stakeholder engagement in the development of a European tobacco control tool. Health Policy. 2019;123(10):917-23.

5. Boaz A, Chambers M, Stuttaford M. Public participation: More than a method? Comment on “harnessing the potential to quantify public preferences for healthcare priorities through citizens’ juries”. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2014;3(5):291-3.

6. Oliver S, Roche C, Stewart R, Bangpan M, Dickson K, Pells K, et al. Stakeholder Engagement for Development Impact Evaluation and Evidence Synthesis 2018 [Available from: https://cedilprogramme.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Stakeholder-Engagement-for-Development.pdf.

7. Schut M, van Paassen A, Leeuwis C, Klerkx L. Towards dynamic research configurations: A framework for reflection on the contribution of research to policy and innovation processes. Science and Public Policy. 2014;41(2):207-18.

8. Shaxson L, Datta A, Tshangela M, Matomela B. Understanding the organisational context for evidence-informed policy-making 2016 [Available from: https://odi.org/en/publications/understanding-the-organisational-context-for-evidence-informed-policy-making/.

9. Farley-Ripple L, Boaz A, Oliver K, Borst R, Zhang X. Mapping the field : Use of research evidence in policy and practice. William T. Grant Foundation; 2018.

10. Nelson J, Campbell C. Using evidence in education. What works now: Policy Press; 2019. p. 131–49.

11. Traynor R, Dobbins M, DeCorby K. Challenges of partnership research: Insights from a collaborative partnership in evidence-informed public health decision making. Evidence and Policy. 2015;11(1):99-109.

12. Wake C, Lokot M. Co-production: an opportunity to rethink research partnerships 2021 [Available from: https://odihpn.org/blog/co-production-an-opportunity-to-rethink-research-partnerships/.

13. Georgalakis J. Policy and research: ‘It’s the relationships stupid!’ 2020 [Available from: https://transforming-evidence.org/blog/policy-and-research-its-the-relationships-stupid.

14. Wehrens R, Bekker M, Bal R. Coordination of research, policy and practice: A case study of collaboration in the field of public health. Science and Public Policy. 2011;38(10):755-66.

15. Swain S. The Knowledge Exchange Framework must recognise that knowledge comes in all shapes and sizes 2021 [Available from: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/knowledge-exchange-takes-all-shapes-and-sizes-the-kef-must-reflect-that/.

16. Boaz A, Hayden C. Pro-active Evaluators: Enabling Research to Be Useful, Usable and Used. Evaluation. 2002;8(4):440-53.

17. Nilsen P, Ståhl C, Roback K, Cairney P. Never the twain shall meet? – a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science. 2013;8(1).

18. Fraser A, Baeza JI, Boaz A. ‘Holding the line’: a qualitative study of the role of evidence in early phase decision-making in the reconfiguration of stroke services in London. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2017;15(1):45.

19. Harry J, A J, Nicola. Knowledge, Policy and Power in International Development: A Practical Guide: Policy Press; 2012.

20. Hanney S, Kanya L, Pokhrel S, Jones T, Boaz A, Organization WH, et al. What is the evidence on policies, interventions and tools for establishing and/or strengthening national health research systems and their effectiveness?2020.

21. Frost H, Geddes R, Haw S, Jackson CA, Jepson R, Mooney JD, et al. Experiences of knowledge brokering for evidence-informed public health policy and practice: Three years of the Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research and Policy. Evidence and Policy. 2012;8(3):347-59.

22. Boaz A, Oliver K. Building new bridges between research and policy during a national lockdown 2020 [Available from: https://www.upen.ac.uk/blogs/?action=story&id=179.

23. Bayliss HR, Wilcox A, Stewart GB, Randall NP. Does research information meet the needs of stakeholders? Exploring evidence selection in the global management of invasive species. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2012;8(1):37-56.

24. Haunschild R, Bornmann L. Can Twitter data help in spotting problems early with publications? What retracted COVID-19 papers can teach us about science in the public sphere 2021 [Available from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2021/08/09/can-twitter-data-help-in-spotting-problems-early-with-publications-what-retracted-covid-19-papers-can-teach-us-about-science-in-the-public-sphere/.

25. Oakley A, Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. The politics of evidence and methodology: lessons from the EPPI-Centre. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2005;1(1):5–32.

26. Boaz A, Blewett J. Providing Objective, Impartial Evidence for Decision Making and Public Accountability. 2021.

27. Boaz A, Blewett J. Providing objective, impartial evidence for decision making and public accountability. The SAGE handbook of social work research. 2010:37–48.

28. Carey G, Dickinson H, Olney S. What can feminist theory offer policy implementation challenges? Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2019;15(1):143-59.

29. Hawkins B, Parkhurst J. The ‘good governance’ of evidence in health policy. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2016;12(4):575-92.

30. Gough D. Weight of Evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research Papers in Education. 2007;22(2):213-28.

31. Cairney P, Kwiatkowski R. How to communicate effectively with policymakers: combine insights from psychology and policy studies. Palgrave Communications. 2017;3(1):37.

32. Boaz A, Baeza J, Fraser A, Group tEISC. Effective implementation of research into practice: an overview of systematic reviews of the health literature. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4(1):212.

33. Marceta JA. Evidence-based policy as a political ideal 2020 [Available from: https://transforming-evidence.org/blog/we-should-question-presentation-of-evidence-based-policy-as-a-political-ideal.

34. Francis M. Increasing capacity for policy engagement through training and partnership 2020 [Available from: https://www.upen.ac.uk/blogs/?action=story&id=173.

35. Newman K, Fisher C, Shaxson L. Stimulating Demand for Research Evidence: What Role for Capacity-building? IDS Bulletin. 2012;43(5):17-24.

36. Stewart R. A theory of change for capacity building for the use of research evidence by decision makers in southern Africa. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2015;11(4):547-57.

37. Metz A, Boaz A, Powell BJ. A research protocol for studying participatory processes in the use of evidence in child welfare systems. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2019;15(3):393-407.

38. Oliver K, Lorenc T, Tinkler J. Evaluating unintended consequences: New insights into solving practical, ethical and political challenges of evaluation. Evaluation. 2020;26(1):61-75.

39. Boaz A, Fitzpatrick S, Shaw B. Assessing the impact of research on policy: a literature review. Science and Public Policy. 2009;36(4):255-70.

40. Pielke RA. Usable information for policy: An appraisal of the U.S. Global Change Research Program. Policy Sciences. 1995;28(1):39-77.

41. Norton GW, Alwang J. Policy for plenty: Measuring the benefits of policy-oriented social science research. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute; 1997.

42. Rosenberg W, Donald A. Evidence based medicine: an approach to clinical problem-solving. BMJ. 1995;310(6987):1122-6.

43. Hopkins A. ‘Pushing’ research evidence gets us only so far 2020 [Available from: https://transforming-evidence.org/blog/pushing-research-evidence-gets-us-only-so-far-with-linear-approaches-having-sever-limitations.

44. Says S. To shape policy with evidence, we should celebrate both good practice and good theory 2021 [Available from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2021/01/20/to-shape-policy-with-evidence-we-should-celebrate-both-good-practice-and-good-theory/.

45. Boaz A, Gough D. Complexity and clarity in evidence use. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2012;8(1):3–5.

46. Rivas C, Tomomatsu I, Gough D. The many faces of disability in evidence for policy and practice: embracing complexity. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2021;17(2):191–208.

47. Rickinson M, Cirkony C, Walsh L, Gleeson J, Salisbury M, Boaz A. Insights from a cross-sector review on how to conceptualise the quality of use of research evidence. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 2021;8(1).

48. van der Graaf P, Cheetham M, Redgate S, Humble C, Adamson A. Co-production in local government: process, codification and capacity building of new knowledge in collective reflection spaces. Workshops findings from a UK mixed methods study. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2021;19(1).

49. Kenny C, Gough D, Tripney J. Approaches to Assist Policy–Makers’ Use of Research Evidence in Education in Europe. Empires, Post-Coloniality and Interculturality: Brill Sense; 2014. p. 117–33.

50. Bradshaw T. The government needs to deliver on its promises on research 2019 [Available from: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/the-government-needs-to-deliver-on-its-promises-on-research/.

51. Oliver K, Hopkins A, Boaz A, Guillot-Wright S, Cairney P. What works to promote research-policy engagement? 2020.

52. Oliver S, Gough D, Copestake J, Thomas J. Approaches to evidence synthesis in international development: a research agenda. Journal of Development Effectiveness. 2018;10(3):305-26.

53. Topp L, Mair D, Smillie L, Cairney P. Knowledge management for policy impact: the case of the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. Palgrave Communications. 2018;4(1).

54. Metz A, Boaz A, Robert G. Co-creative approaches to knowledge production: what next for bridging the research to practice gap? Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2019;15(3):331-7.

55. Lancaster K, Rhodes T, Rosengarten M. Making evidence and policy in public health emergencies: lessons from COVID-19 for adaptive evidence-making and intervention. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2020;16(3):477-90.

56. Geyer R, Cairney P. Handbook on Complexity and Public Policy: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2015.

57. Oliver K, Lorenc T, Tinkler J, Bonell C. Understanding the unintended consequences of public health policies: the views of policymakers and evaluators. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1057.

58. Hanney SR, Kanya L, Pokhrel S, Jones TH, Boaz A. How to strengthen a health research system: WHO’s review, whose literature and who is providing leadership? Health Research Policy and Systems. 2020;18(1).

59. Walker A, Boaz A, Hurley MV. The role of leadership in implementing and sustaining an evidence-based intervention for osteoarthritis (ESCAPE-pain) in NHS physiotherapy services: a qualitative case study. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2020:1–8.

60. Rycroft-Malone J, Wilkinson J, Burton CR, Harvey G, McCormack B, Graham I, et al. Collaborative action around implementation in Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care: towards a programme theory. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2013;18(3_suppl):13-26.

61. Boaz A, Gough D. Beyond the ‘simple logic’ of evidence-based policy. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2011;7(4):399-401.

62. Boaz A, Baeza J, Fraser A. Does the ‘diffusion of innovations’ model enrich understanding of research use? Case studies of the implementation of thrombolysis services for stroke. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2016;21(4):229-34.

63. Strassheim H, Kettunen P. When does evidence-based policy turn into policy-based evidence? Configurations, contexts and mechanisms. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 2014;10(2):259-77.

64. Williams J, Rychetnik L, Carter S. Evidence-based cervical screening: Experts’ normative views of evidence and the role of the ‘evidence-based brand’. Evidence and Policy. 2020;16(3):359-74.

65. Campbell D, Donald B, Moore G, Frew D. Evidence check: Knowledge brokering to commission research reviews for policy. Evidence and Policy. 2011;7(1):97-107.

66. Ward VL, House AO, Hamer S. Knowledge brokering: Exploring the process of transferring knowledge into action. BMC Health Services Research. 2009;9(1):12.

67. Breckon J, Gough D. Using evidence in the UK. What Works Now?: Evidence-Informed Policy and Practice. 2019:285.

68. Heckels N. Research should be at the heart of government 2020 [Available from: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/research-should-be-at-the-heart-of-government/.